PPBlessing: How did you get into writing?

Benny: It has been a step by step growth throughout the years. I think the interest started growing when I was still in primary school writing compositions as assignments for the English lessons. At that stage I did not make much out of it, though I continued writing occasionally, until way later after college when I took writing a bit more seriously.

PPBlessing: Can you remember the year you took writing seriously? What necessitated the change?

Benny: It was very progressive to be honest. In 2015, with the establishment of WhatsApp I started writing poems to my friends with this new app that could allow chatting. In 2016, I wrote a verse which I posted on Facebook. I would need to check what it was all about. In 2017, I wrote and posted poems on Facebook regularly which led to a steady growth in followers. I still had not identified myself as a writer, though everyone else actually thought I was at the end of that year.

PPBlessing: When did you identify yourself as a writer?

Benny: At the end of 2017.

PPBlessing: You’ve been an editor for the Writers Space Africa magazine and one-time country coordinator of Writers Space Africa (Kenya chapter), in what ways has working in these capacities challenged you?

Benny: In many ways. I will recall the highlights. When I joined Writers Space Africa (WSA) magazine as a poetry editor, I had not necessarily worked with a group of African writers before, especially those with serious diverse mindsets on thematic approaches such as the ones we published in the magazine. We had to discuss whether to publish poetry with controversial themes, for example. At such times inclusion was a particular consideration to solve different perceptions that emanated from different editors.

It was a bit different for Writers Space Africa (Kenya chapter). I came to the limelight in a very sensitive season when Wakini Kuria was ailing and when in a year’s time we were just about to host the African Writer’s Conference (AWC) 2019 in Nairobi. I pushed for the small group of writers that Wakini had brought together to meet in person. Only four out of about ten members met, but this little start gave us the foundation that we needed to build what became a group of 70 writers in three years. Sadly, Wakini Kuria passed on before she could see the fruits of what she established. We managed to host the AWC 2019, establish the first country chapter of WSA, and registered with the government. None of this was a walk in the park but thanks to the leaders who worked together resiliently.

PPBlessing: Let’s talk about your poetry collections, Phases of Life and After Sunset. What inspired them and why did you choose to publish both of them at the same time?

Benny: Phases of Life speaks of the hope that exists in God for every human as they navigate through various seasons of their lives. The muse was hope!

After Sunset has an African inclination as a result of working with many African poets over a period of time. The poems in the collections were written between 2018 and 2019.

In November 2019, when I had taken a six-week career break, and with more time to myself, I sorted my poems. I had about 250 written poems then, and picked about a hundred which I divided as per the theme of each book. And the collections were born.

PPBlessing: Seeing that you still have a ton of poems left, when should we expect another collection?

Benny: I have an unpublished collection titled ‘Wings’ developed before the twins, ‘Phases’ and ‘Sunset’ as I call them. I am working on a Pantoum collection. Maybe I need another 6-week break to work on this and something extra.

PPBlessing: So when are you taking the break so we can mark our calendars for another release from you?

Benny: I have big plans for next year. I will keep you posted, follow my Instagram page @BennyWanjohi for that and more.

PPBlessing: Why did you choose a hard-cover publication for your twins instead of the digital publication which is more common now?

Benny: There is a sense in which the smell of books is captivating to readers. I was also looking forward to holding my first tangible publication, as petty as this might sound. Interestingly, the demand is still high even after a fast-paced sale of about 500 copies. My team and I are trying to work on the next consistent publication. We also have plans in the pipeline to have e-copies available on various platforms such as Amazon.com.

PPBlessing: Godspeed on that. How did the Benny poetry style come about?

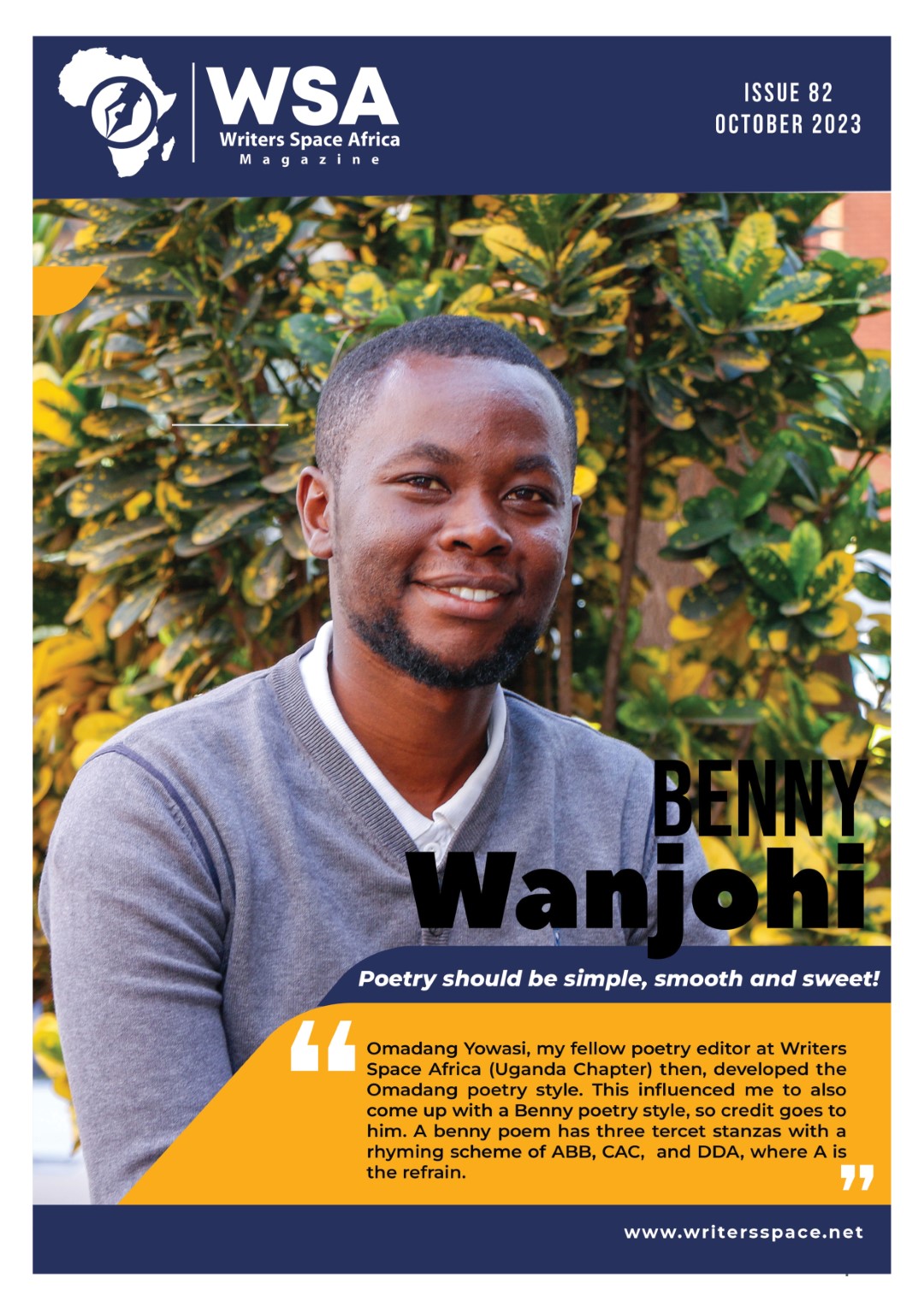

Benny: Omadang Yowasi, my fellow poetry editor at Writers Space Africa then, developed the Omadang poetry style. This influenced me to also come up with a Benny poetry style, so credit goes to him. A benny poem has three tercet stanzas with a rhyming scheme of ABB, CAC, and DDA, where A is the refrain. I always had this poem in the editorial notes of almost all 11 editions of PoeticAfrica during my tenure as the Chief Editor.

PPBlessing: During your time as chief editor, what were some of the significant contributions PoeticAfrica made to the African literary landscape?

Benny: The establishment of the magazine was a great platform for poets in Africa to showcase their great poetic talents. PoeticAfrica offered this chance to hundreds of poets whose poems were published in these three years that I’ve served as Chief Editor of PoeticAfrica. It was not necessarily possible to offer developmental editing due to the high number of entries that were coming in for each edition. Therefore, a lecture section was included to offer a learning platform in areas that the team was identifying. The interview’s section also allowed the voices of known and unknown poets to come to the limelight which was a marketing arena for their poetry careers. Notably, the magazine also sponsored poetry events from time to time.

PPBlessing: Could you mention some of these sponsored events?

Benny: Just to mention a few that come to mind is the Octofest Poetry 2022 and 2023, African Writers Conference, among others.

PPBlessing: PoeticAfrica is known for being a trilingual magazine. How did you manage the unique challenge of publishing in multiple languages, and what impact did this have on the magazine’s readership?

Benny: We are the first to go trilingual. We went fully on this once we decided that it would be one of our unique pillars. We wanted to increase readership and had to make the hard decisions to settle on the three languages spoken by majority of Africans, while appreciating that there were other languages that were widely spoken which were not our preference publication languages for particular reasons. At some point we did a research on who was downloading our magazine after this move and to our surprise we had a long list of about 40 countries from all across the world.

PPBlessing: In your opinion, what is the significance of having a trilingual magazine like PoeticAfrica in Africa’s literary landscape, and how did it contribute to fostering unity among diverse linguistic communities?

Benny: It is like serving a buffet meal. No one in the party is left out. Furthermore, French poets were thriving especially in particular Francophone countries like Cameroon and Rwanda. Kiswahili poetry named ‘mashairi’ has existed, and largely developed over the years. Africa is one and all these African verses needed one home which PoeticAfrica offered.

PPBlessing: Were there any specific themes or issues that you felt were particularly important to address during your time as chief editor, and how did you approach them?

Benny: The prominent one was the definition of African poetry. What did it exactly mean when we talked about African poetry? Over the years, I have observed that poets differ greatly on this issue. Particularly two schools of thoughts exist; one which believes that African poetry must include themes like thatched huts, semi-naked Africans dancing around a night fire, unschooled boys grazing etc. The other school believes in themes like African modern homes in the village that have electricity, cooking stoves, children who go to schools in towns by bus, working parents who come home in the evening etc.

Any enthusiast of literature must appreciate the existence of both and appreciate that a majority of Africans are adapting to the trends of industrialization and the outplay of technology. Poets have the freedom to write from either traditional approaches or contemporary approaches to African poetry. Readers and audiences must also be allowed to interact with their historical past while embracing the inevitable modernity settings in Africa.

PPBlessing: A balanced perspective is always very important.

As a Kenyan, how do you think your background and experiences influenced your editorial approach at PoeticAfrica, particularly in representing African voices?

Benny: There is what we call editorial bias and country writing styles and preferences. I am not an exception to these biases and preferences.

Firstly, to avoid this trap we were keen to specify, on all our calls for submissions, what we were looking for in the entries sent to PoeticAfrica. These provided a guideline of selection.

Secondly, I worked with a vibrant team of poets from all across Africa who all edited and made first selections of poems before these came to my desk. We made it very easy to challenge each other on which submissions we selected. I would always share my final selection for editors to review and occasionally, I was put on the hot seat to explain the final choice of selected entries. So, at the end it was never a Benny’s voice, but a voice of Africa, handled carefully by this entire team of PoeticAfrica editors, that we were releasing out there.

Finally, there are conventional guidelines about poetry that any editorial team for a magazine or publishing house cannot bypass and we were keen to observe these.

PPBlessing: This is great. I believe poets whose works have been rejected will understand better when they get to read this interview.

Beyond PoeticAfrica, you’ve been involved in the African literary scene. Can you tell us about some of your other literary endeavours and how they connect with your role as an editor?

Benny: I worked closely with Anthony Onugba, the founder of Writers Space Africa (WSA), when I was the country coordinator of WSA-Kenya. At the same time, I served in the Board of Trustees of both African Writers Development Trust (AWDT) and Writers Space Africa. As expected of the board, we made a lot of strategic decisions around the growth of the literary scene in Africa through platforms such as African Writers Conference, Penpen Residency, Writers Mingle, and Writers’ Academy. These are events geared to the growth of writers in Africa, giving them not only a platform to interact but to also improve their art.

As an editor, these platforms gave me a chance to contribute through literary conversations, judging writers’ events and competitions, and mentoring upcoming writers. I particularly thank Anthony for these opportunities to make my African literary society better.

PPBlessing: Could you share a memorable moment or article from your tenure that you believe encapsulates the essence of PoeticAfrica’s mission?

Benny: A very recent one is the appearance of Kalekye ‘Mish’ Mirriam in the unveiled Longlist for the 2023 African Writers Awards. Mish has been published by PoeticAfrica severally and has been a mentee of mine. To see her growth to this level was exhilarating, and I was grateful that the platform given to her by PoeticAfrica built her confidence to write and submit more.

PPBlessing: PoeticAfrica has focused on poetry, but it also touches on various forms of creative writing. How did you maintain a balance between different literary genres and styles in the magazine?

Benny: As the title suggests, the idea was to keep it purely poetry. There is an appreciation that poetry does not exist as an oasis in a desert as a genre. Therefore, interviews and lecture articles existed symbiotically in the magazine to compliment poetry. There was no conflict as the best way to present poets was through interviews and the best way to teach poetry was through articles. There was no better chance to display the beauty of diversity in literature and the coexistence of its elements.

PPBlessing: Reflecting on your journey as the chief editor of PoeticAfrica, what were some of the highlights and challenges during your tenure?

Benny: One of the major highlights is the consistency of the founding editorial team: Esv Keks Funmininyi, Nnane Ntube, Christina Lwendo, Lebogang Samson, Chipo Chama, and Liza Akunyili who was our lead interviewer. These editors remained put even in times when the boat threatened to sink in the raging waters of starting a new unknown magazine, inclusion of three languages, low submission numbers a couple times when themes were difficult, heavy discussions on thematic concerns, and so on. They were flexible enough to allow us to establish structures and take on particular chief editorial roles upon themselves. During that season, a few of them also published their own poetry collections.

As earlier mentioned they grew the readership to more than 40 countries in Africa and beyond. A virtual community of poets who submitted their poems and readers who followed us was built. The editions published are now a virtual library on our website https://www.writersspace.net/poeticafrica where generations after us can always go back to for reference for both academic and research purposes, especially if contemporary poetry takes center stage in the future of poetry in Africa.

PPBlessing: As you prepare to step down from your role, what are your hopes and aspirations for the future of PoeticAfrica, and who will be your successor?

Benny: I was keen on structures and laying the foundation which was significant at that stage of the magazine. My successor Keks Funminiyi has the freedom of bringing in his vision. I have already discussed this with him the entire year as I prepared to hand over. We are also working closely together in the next four months of this transition.

That said, I look forward to a time when PoeticAfrica will hold a major competition for African poets, come up with anthologies, a residency and probably establish the biggest online and physical poetry libraries in Africa with faculties in the three languages. We believe that God who started this work will bring it to fulfillment.

PPBlessing: Amen. I’m looking forward to this time too.

How do you see the future of African literature evolving, and what role do you believe PoeticAfrica will play in shaping that future? Aside these that you’ve mentioned above.

Benny: African writers are more keen, than ever before, on mergers and platforms like the annual African Writers Conference are helping achieve this. While this is not without hurdles, it is speaking of a united African literature voice to a global audience. PoeticAfrica and other literary platforms are the labour pains towards this future.

PPBlessing: What message would you like to convey to the readers, contributors, and supporters of PoeticAfrica as you conclude your tenure as chief editor?

Benny: Poetry should be simple, smooth and sweet!

PPBlessing: Wow! A short and simple poetic message.

What advice do you have for emerging writers and poets in Africa who aspire to get their work published in reputable literary magazines like PoeticAfrica?

Benny: Each magazine is particular with their requirements and taking note of this is key. Also check out the writing styles of the various editors and any interviews or conversations they engage in. Learn what they want to see in a poem and tweak your work towards that, especially for established poets. Upcoming poets can always find mentors who look at their work before they submit.

PPBlessing: Aha! Do you have a personal editor and mentors?

Benny: I have peer mentors. Christina Lwendo and Omadang Yowasi edit any work I am publishing while Anthony Onugba is my proofreader.

PPBlessing: Which writers have had the most influence on you and your writing?

Benny: Christina Rossetti, an English poet and Dante Alighieri, an Italian poet. They were both greatly talented ancient poets who acknowledged God as their help in their writing. It has been the same for my case, without Jesus no poem of mine could have seen the light of day.

PPBlessing: How have you been able to combine ministry and the diverse work you do in the literary scene?

Benny: I use a concept I call block-working. I compile tasks that are doable together and finalize that in one sitting, probably with tea-breaks. My day is divided in an 8-8-8 hours pattern. That is office work, free time and sleep time. My free time is not really free since it is pre-occupied with studies and church ministry.

PPBlessing: What are your hobbies?

Benny: Riding motorbikes, mountaineering, and graphic designing.

PPBlessing: If you were to change one thing in your writing journey, what would it be?

Benny: I would have started earlier.

PPBlessing: What role has being part of a literary community played in your writing and editing journey?

Benny: From the responses above, it is obvious that I owe my writing and editing journey to Writers Space Africa, Writers Space Africa (Kenya chapter), PoeticAfrica and Friendswhowrite, a former group of writers that I belonged to. There is a wealth of knowledge that other writers have which I have benefited from. For example, my works have been critiqued and I have a found a platform of like-minded writers and readers. I would be miles behind in this journey if I never joined these communities.

PPBlessing: Aside poetry, do you also write other genres?

Benny: I write poetry 70% of the time. There are a few occasions when I am writing research publications and development programs.

PPBlessing: What inspires you?

Benny: God is my inspiration all the time! There are times I experience writers’ block and make short prayers that unblock it. He is my muse in many different ways.

PPBlessing: What do you intend to achieve with your writing?

Benny: I hope that in my short life here on earth and many years after I am gone, people will read my works and find hope to live afresh in this world of ups and downs. That the poems will evoke them to happiness, love, kindness and reason of their worth as humans.

Read – Autricia Timti – Winner of the 2021 Young English Cameroonian Writers Awards (YECWA)