This interview is By Nyasili Atetwe

—

Your name is fascinating – Gankhanani Moyo. What does it mean in your language?

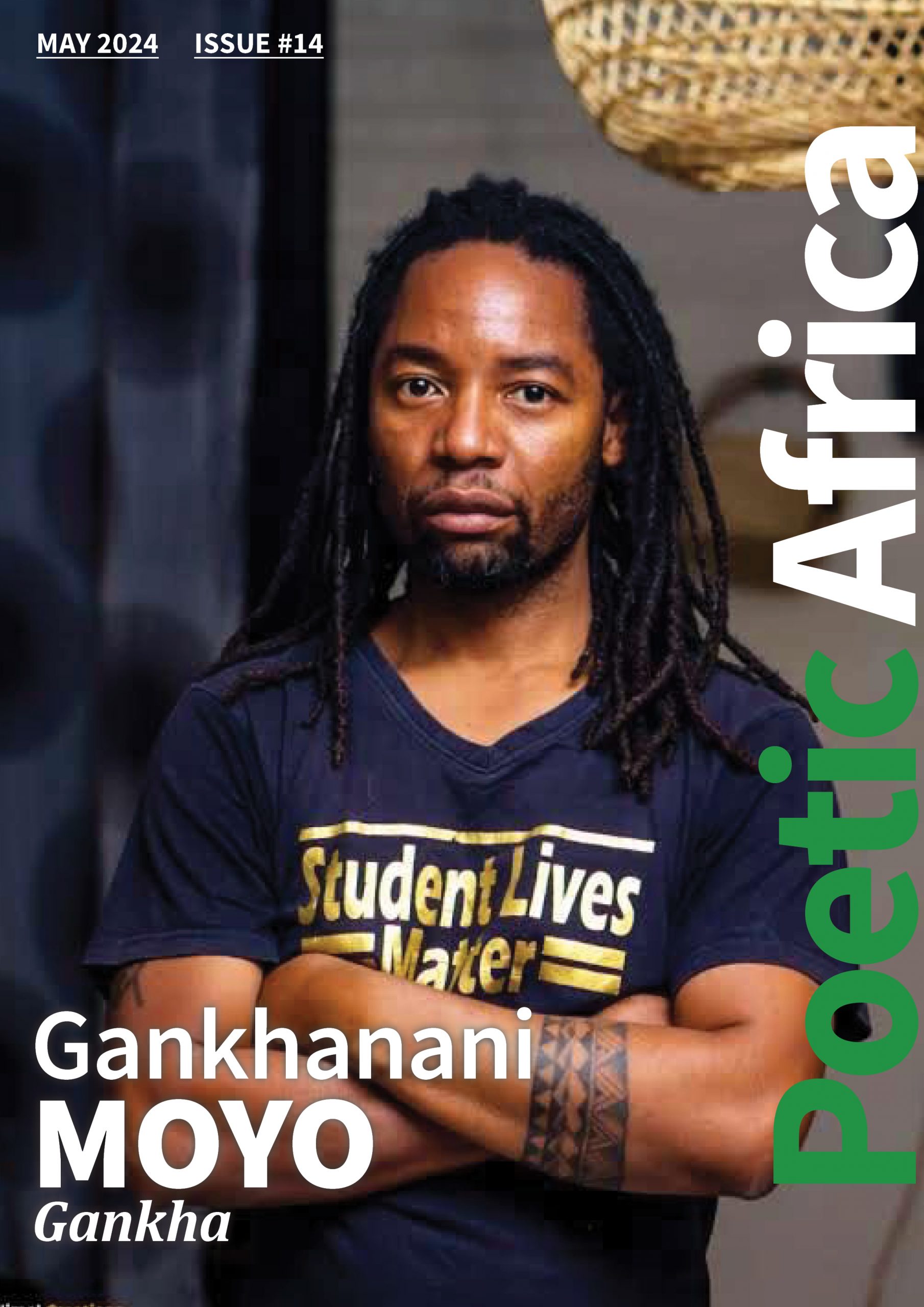

I have always had a challenge telling people what my name really means. First, let me state that my official name is Moffat Moyo, and I hate the name Moffat. I find it offensive when someone calls me Moffat, especially when they know that the name my spirit resonates with is Gankhanani. They lose nothing when they call me Gankhanani or Gankha, in short.

At birth, I was named Gankhanani Moffat Moyo after my grandfather. However, the Africans in the society rejected Gankhanani and opted to go for Moffat, which they found to be fancy. Gankhanani is a militaristic name that means bitterness (something that cannot be easily eaten). Due to its bitterness, the name cannot be touched, let alone tasted or even tested, by its enemies. The name Gankhanani, therefore, represents someone who is a victor, one whose enemies can’t come near, and he ends up being a go-getter. Gankhanani goes for what he wants, and he always gets it regardless of the circumstances.

So who is Gankhanani Moyo? What’s the one thing nobody knows about you?

I have always had problems talking about who Gankhanani is. I am a Zambian young man aged 44 who is both an artist and an arts and cultural teacher. I write, I perform, and I teach what I do. Most importantly, I am a father to four girls (Nthangana, Dabilani, Madaliso, and Ungweru) and one boy, also called Gankhanani.

What does poetry mean to you personally, and how do you define your unique style or voice as a poet?

Poetry is a special kind of language. I rarely see poetry as a literary genre; I see it as a language, a medium of expression that uses its conventions because its function is to tell it differently. The role of poetry is to touch the deepest emotions and take the audience to the furthest of perceived reality.

I don’t think I have a defined voice yet. I am still searching, and I believe every poet always searches for their voice. Their voice is only found once the chapter on their physical life is closed. When the poet transitions to the other realm, we can easily put a tag on their voice. While they are still here with us, their voice is always wandering about and wondering what their identity really is.

Read – Interview with Scholastica Moraa

How far back have you gone since you sat down and decided, well, I want to do poetry, for better or worse?

I don’t remember ever deciding to be a poet. I don’t remember deciding to become a writer, an actor, or a dancer. I never even planned to become a teacher. I think that I probably already was, and the Universe merely placed me in the space that actualized the unseen reality. I have been an avid reader since I was in Grade 1. I read whatever I came across. Even the paper on which the fritter’s seller wrapped the fritter was reading material to me. Even the newspaper left in the toilet to function as toilet paper was reading material before it is dispatched for eternity. I read so much that my world was more in books than outside. I grew up in the village in the depths of Lundazi, in Eastern Zambia. Walking back from school almost always was a reading space for me. I can’t remember how I managed it, but I read while walking from Manyi Primary School to my village. In the evening, I shared stories I had read during storytelling sessions.

Whenever I read poetry, I had no idea it was called poetry. All I remember was that I enjoyed reading it because it sounded and felt good. So, when I learnt that whatever I used to read, particularly fiction, never really happened but was imagined by someone and shared through the written form, I got the motivation to write. I can’t remember the first piece I wrote and when exactly. But it was sometime in 1992, when I was in my fifth grade, that I started writing. I started with fiction, retelling oral prose narratives and jokes before transitioning into poetry. In the poetry, I found it easy to vent.

I am a very emotional person. When I get hurt, I really get hurt. I easily cry, and emotion has, at certain moments, almost led me to take my life. I have expressed myself emotionally through poetry and healed from several painful life experiences. So, I can’t remember when I became a poet, but I think I have always been one, and I just realized it at a specific time when I expressed myself as a poet.

Do you write and sing your poems? Is there anything transformative about singing your poems?

Mostly, I sing my poems. I love expressing what I have inside. This is the reason I rarely perform other people’s poetry. I have performed poetry by poets such as Dennis Brutus, Munatamba, Shakespeare, Soyinka, and mainly traditional forms. I have performed poetry by my cousin, Rodrick Mhlanga, who is my main collaborator. But central to my performance is my poetry.

When you perform your poetry, you also become your audience, your observer. You become aware that you are never a single entity by performing your own poetry. There are many entities within you, including the poet, the audience, and the critic. Performing one’s poetry broadens your perspective, not just on your poetry but also on your view of who you are as a living being.

Read – Interview with Liza Chuma Akunyili

Poetry can serve as a medium for branding and promotional work. How have you leveraged your poetic skills for commercial projects or collaborations, and how does this relate to your income as a poet?

One thing I have learnt as a human being and as a poet is not to look for recognition but to do what the Universe has called you to do as a part of the recreation of the reality of the Universe. And when you do what you do, ensure you do the best. My aim in poetry is to create the kind of poetry that speaks the most and the deepest of me. Therefore, I do not look forward to being recognized as a poet or any kind of artist. I always think that my work is supposed to speak. When I first did ‘The Lab of Poetry’ (2005), a poetry album (I don’t have a single copy of the work save for two pieces on YouTube) with my friends, my whole desire was to create a different kind of poetry. Those who had a chance to listen to it thought it was a novel idea. It wasn’t commercially successful at all, but the fact that I had such a product out there and people were interacting with it was crucial.

Regarding financial benefit, when I published my first book, Songs from My Soul (2008), I never thought it would sell as it did. It was impressive because whenever I went to the booksellers at the end of the month for about a year or three, I returned with a cheque or cash, meaning there was some commercial success in poetry. My second book, Orgasm (2011), was received with mixed feelings because of the shocking title. I have to mention, again, that the title was deliberate. I love surprising people, including my audience. People wanted to read Orgasm, but mostly in private because, it appeared, they did not want people to see them reading such a book whose title had pornographic connotations. By the way, Orgasm is not pornographic at all. It is primarily modernist and philosophical, though a collection of poetry and fiction.

My latest offering, a collaboration with Rodrick Mhlanga, is a poetry high-budget CD, Tisamale Zambia (2022), by Gankhanani and Archbishop (https://music.apple.com/zm/artist/gankhanani/1637127439). We deliberately worked with accomplished music producers such as Jerry Fingaz, Skills, Mic, and Ericado, and musicians such as Mathew Tembo, Maureen Lilanda, Mumba Yachi, James Sakala, Theresa Ng’ambi, P Mike, and Chisomo. The idea was to share a poetry collection with the world that was different from how poetry is traditionally offered.

The next project will be remarkably different from the last one in that it will be a full narrative presented through different poems. I hope those who will interact with the work will enjoy it since I aim to give the audience something they can enjoy one day. I am also putting together most poems from Orgasm and new poems for a collection. However, having not decided on the form the collection should take, I am still holding on to it. As I said, every work that comes out should be different. There should be a reason for paying attention to your work, not just because of your name. The actual work of art should move audiences and not the work’s creator.

For this reason, the creator has to take all the time before releasing their products to the public. To me, that’s what branding is in the art world. That’s how I have branded myself, an artist with no brand but one that serves purposes crafted by the Universe.

Read – Interview with Wangui Kimani

Finding one’s unique voice in poetry can be a lifelong quest. How have you cultivated your distinctive poetic voice, and are there qualities or themes you believe define it?

As I said earlier, I don’t think I have a distinct voice. I think I say what should be said, except an artist should not say what has to be said the way everyone else says it. While that might be taken to mean a distinct voice by others, to me, it means that your voice can be pretty fleeting and oscillate between different centers according to prevailing circumstances. While I agree that there is a need to have an identity, I also feel that identity, like voice, is not only subjective but also an ephemeral concept. Our identities are so fluid that we cannot pin them down. Haven’t we seen people like Ngugi and me, among others, who have changed names? People who have changed geographical locations? People who have changed languages? People who have changed status from single to married and even back to single, widowed, divorced, or undefined? Have we not seen someone with several identities, such as father, teacher, mother, son, daughter, and so on, within the same physical form? Identity cannot be boxed; neither can voice.

For this reason, I think that I have no unique voice. I think that after I have ceased to be physically, someone will look at my poetry and have a somewhat definitive identification of it. But I can say, almost certainly, that what one will see as the voice of a particular poet can also be taken not to be so by another. So, what are my unique themes and voice? I think it’s the unfinalisable, the unrecognisable, and the inscrutable. I think the blank spaces carry more than the filled ones. I think the silence could be more definitive than the spoken. My voice could be my inability to be definite.

Do you have a writer or specific mentor who has played a pivotal role in your development as a poet, and how they influenced your work?

Oh, there are many. As a literature student, I have read many, and they have all contributed to me in one way or another. Some people have directly shaped my creative writing. The late Professor Mapopa Mtonga shaped me to consider traditional elements in my work, while Dr. Cheela Chilala, my colleague, shaped me on literary elements, particularly rhythm. My late lecturer and later colleague, Panwell Munatamba, influenced me in terms of the use of metaphorical language, particularly as realized in his earlier poetry. The same can be said of the poetry of Wole Soyinka and Dennis Brutus. Edgar Allan Poe is another poet who influenced not just my poetry but also my prose. His The Raven and Annabel Lee are amongst my favourites of all time.

Poetry has a long history of featuring controversial and provocative themes. Have you ever written a poem that has sparked debate or controversy due to its subject matter, and what did you aim to achieve with that work?

I once wrote a poem entitled ‘Jack of All Trades,’ which was published in one of the local newspapers and received a response. That was in the early 2000s. In Songs from My Soul, I have ‘The Signing Ceremony’ that talks about debt, which I called the ceremony the signing ceremony of the death pact. Most of my students singled it out as the most forceful and politically-charged poems. My book itself, Orgasm, was received with mixed feelings due to the title and my desire to shock. I don’t remember writing to get a specific reaction or get people to debate. I believe that sometimes, the work written today will only find its reader after 500 years. So, the fact that people are not responding does not mean the work is empty. It could mean that its audience hasn’t yet come across it.

The deliberate and intentional titling and naming of things is indeed captivating ( e.g, orgasim)