This interview is By Nyasili Atetwe

—

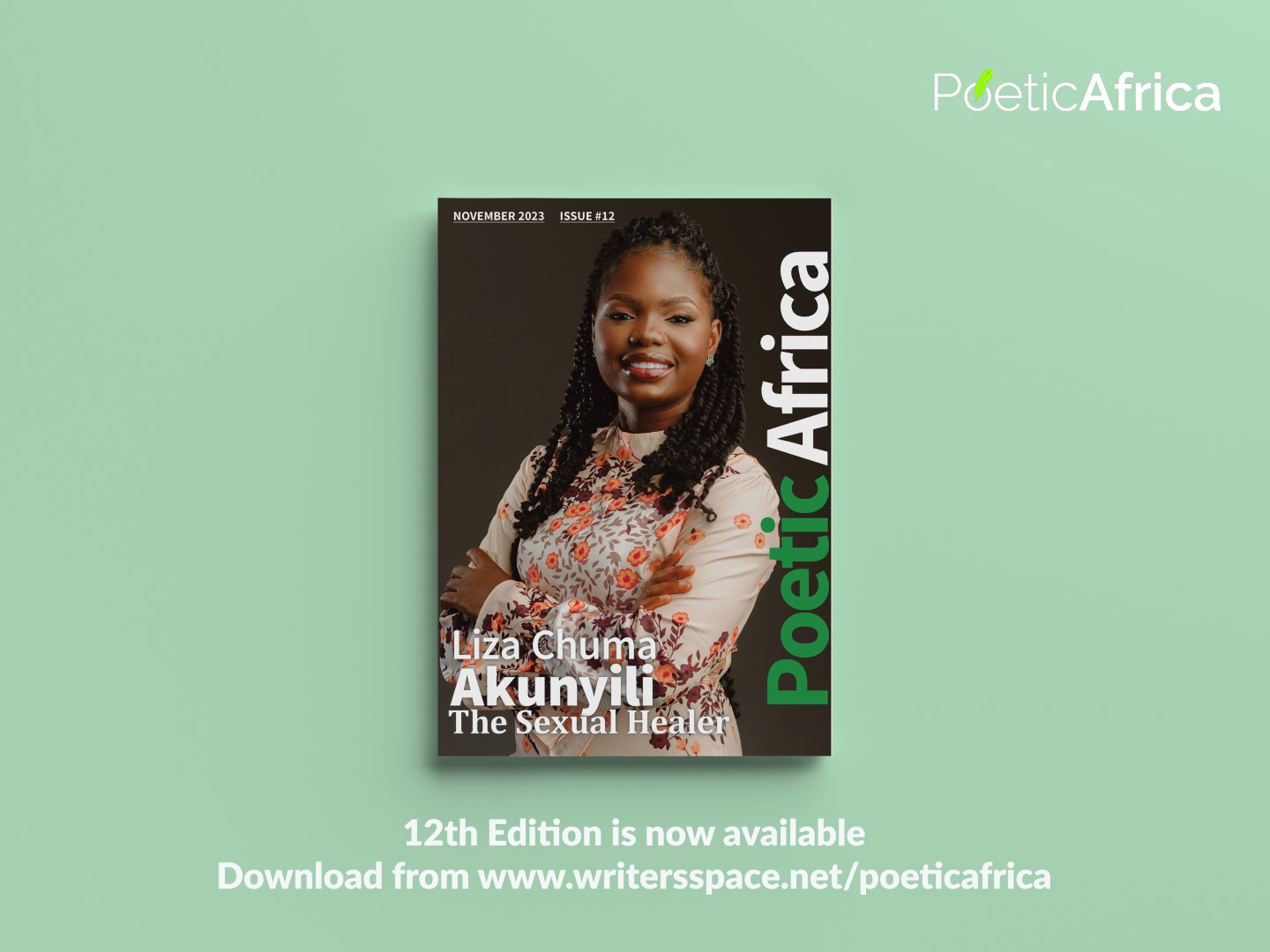

Who is Liza Chuma Akunyili? What’s the one thing nobody knows about you?

Liza is a girl (that’s my favourite definition in recent times in a world where pressure never stops coming). Laughs. Why should I announce it in a magazine if nobody knows about it?

That’s on a lighter note. I realised I was a songwriter for at least eight years before I realised I could be a good poet.

You’re commonly known as Liza Express (at least in Writers Space Africa circles). Why Liza Express?

It literally means “Expressing Liza.” However, my sex therapy business now officially answers the name as it started with me trying to give my clients the space to express themselves regardless of previous trauma and present addictions.

Read – Interview of Wangui Kimani

When did you sit down and say, “now I need to get serious about writing poems?”

- My friend, Iyanu Adebiyi (an amazing spoken word poet), came into my room and saw a stack of diaries. Out of curiosity, she asked what they were for, and I mentioned the different topics and got to my abandoned poetry diary (I wasn’t a poet at the time, but I had attempted). She inspired me, and I tried out more Shakespearean poems (I used to love Elizabethan English).

Have you published any of your poetry?

Yes, I publish online via Medium, but I also have a short collection of forty one-liner poems online called “Monostich Love” that is dedicated to the Man I hope to pamper. You should check it out – it’s cheesy and funny.

Do you do any other kind of writing aside from poetry?

Yes. I’m presently returning to academic writing.

What life experiences and events have shaped you as a poet?

Chaos. Wanting to help people express themselves and love inspired me to work with people. Realizing they were stuck in their traumatic experiences inspired me to become a therapist. However, it is insisting on the beauty of life instead of just soaking in the negativity and chaos that makes a poet. I call it finding “Beauty in unlikely places.” I would write a collection based on that theme.

Poetry often explores themes of identity. How does your personal identity inform and intersect with your poetry?

The older I grew, the more I realized society was insistent on making an adult out of me before I should have become one. As I reconnect with the girl in me and relearn to twirl in the rain, I pour this joy on pages and call them poetry, even if they don’t have length.

Many poets draw inspiration from other art forms or literary works. Are there particular books, authors, or artists who have influenced your poetry?

Iyanu Adebiyi – Wonder Poetry Album, Khaled Hosseini – A Thousand Splendid Suns, Anthony Onugba writer’s community (WSA), and his creative content, amongst others.

Read – Interview with Nurka Slam (Nuru Kakore)

Artists undergo periods of self-discovery and evolution in their craft. What were the significant moments in your poetry journey when you felt a fundamental shift or transformation in your style or perspective?

The first one was at a writer’s meetup in 2011 when I complained about poetry being confusing. The poetry coach explained that poetry was freedom, and she used an example I’d never forget: “In my dreams, I’d be right.” It wasn’t a straight sentence, and I loved the rhythm in my ears. I’ve gone on to love poetry with great rhythm and fantastic use of poetic license.

Another shift was performing at my friend’s birthday and realizing I could verbalize my poetry – it had presence.

Another was performing my first fully memorized piece (I didn’t continue with this, but I knew I could do it if I ever had to, and that killed the fear of creating poetry that wasn’t amazing).

Lastly, I discovered I could compress whole poems into one line. I’m still in my Monostich Era. At some point, I’d revisit these poems and make them longer (if need be).

You speak Yoruba, Ebve, Igbo, and English (with varied proficiency in each of these languages). Have you ever explored writing poetry in multiple languages? What are the unique challenges or opportunities that multilingualism offers in poetry?

Unfortunately, I haven’t explored writing poetry in any language besides English.

Maya Angelou wrote, “I know why the caged bird sings.” Can you discuss the significance of using metaphors and symbolism in your poetry and how they help convey deeper meanings?

Without metaphors and symbolism, poetry reads like an article. Many times, a story is lodged in a poem, but you want to say it without giving it away, plus you’re inviting the reader’s mind to a dance. The ability to give the reader something to meditate on after they’ve closed your book is something every poet needs. But you cannot achieve that by showing them – you achieve that by encoding it into an experience they can relate to.

By this logic, you will realize that some symbols will make sense in a Kenyan poem but not in Nigeria.

The questions you need to ask yourself when using metaphors and other elements are, “who is my audience, and can they relate to this?”

If this piece is to expand beyond my target audience, would this new audience comprehend these metaphors, or would I have to interpret them?

Litmus test: If you have to interpret your poetry to the reader or listener, your language is inappropriate for that audience, or your ability to communicate to them needs to be worked on a bit more.

Read – Interview with Funminiyi Akinrinade “Esv_Keks”

In “A Song of Myself,” Walt Whitman largely talks about his identity. He says, “I celebrate myself and sing myself.” I know you use your poetry for self-expression. Do you also use it for self-celebration?

Yes, I do. My self-praise comes to me many times as flows, outstanding one-liners and one-stanza pieces. Sometimes, they extend from poetry and become stories.

Like many artworks, poetry is often associated with passion and artistic expression rather than financial gain. How do you balance your love for poetry with your desire to earn money from it?

I wanted to earn money from it at some point, and I kept getting stuck. Then I slowed down and realized everything else was already monetised – my poetry didn’t need to get monetised either.

Poems can address social, political, and cultural issues that are considered contentious. Do you think these issues censor you as a poet? How do you navigate the potential backlash or criticism that may arise when your work touches on divisive topics?

I haven’t written anything sensitive yet, as my poetry in the last four years has focused on beauty. My work as a therapist brings me knowledge of social ills such as sex trauma, addictions, broken marriages, and abandonment issues. When I’m done with all that negativity, I want to sit with more beauty that keeps me grounded, even if I have to create that beauty myself in a poem.

Some poems are cryptic in language and meaning and, therefore, inaccessible to the common reader. What is your take on the balance between crafting poems that challenge readers and poems that provide clear, accessible messages?

If you’re going to write cryptic poems, write them so frequently that your work teaches itself to the reader. Publish often, retain your language style and energy, and tell your stories in the same format. Literally, create your lingua and bring us into it.

As the world changes rapidly, what should poets do to respond to current events and shape the collective consciousness of society in the years ahead?

Just writing poems and saving them in our archives is not enough. Deliberately publish your work.

Mind you, AI is getting trained to write. Imagine how sophisticated AI writing would be if poets took it upon themselves to train AI in their preferred poetry style? Not only will the average reader begin to bump into poetic flow subtly – but the art of writing beautiful poetry won’t die out because people shifted from writing whole pieces by themselves.

Beyond just becoming performance poets after a few years of writing, we must seek to leverage the technology of our time and not be afraid to get our work out.

Funny thought: better a plagiarized book than an unpublished book (people will know your name, you’ll make some money, you’ll introduce a new generation to poetry, you’ll contribute your quota, you’ll fight for your rights legally). You’ll have more drama that will birth more poetry by publishing than you will by hoarding.

Thank you very much for the opportunity, Nyasili. It’s interesting being on this side of the interview when I’ve been on your side of it for the last three years. Thank you for giving me the experience.